Educator's Podium

Adventures in Minority Recruiting:A Closer Look at Recruiting Minoritiesat Southern College of Optometry

Janette D. Dumas, OD, FCOVD, FAAO

The number of under-represented minorities (URMs) in the profession of optometry is not congruent with the percentage of minority patients optometrists examine in practice.1 Awareness of this mismatch is an important starting point in reducing the gap in health disparities. Minorities report higher rates of patient satisfaction when they receive patient-centered care from racially akin providers, and this link has been observed to enhance health outcomes.2-4

Table 1. Click to enlarge

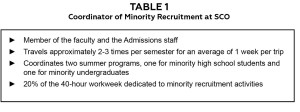

To increase the number of qualified URMs applying to optometry school, Southern College of Optometry (SCO) developed the role of Coordinator of Minority Recruitment. This appointment is designed for a faculty optometrist to become a member of the Admissions staff to recruit at academic institutions and develop enrichment programs with a focus on under-represented minorities. The dual nature of this faculty member/minority recruiter role is unique among the schools and colleges of optometry. (Table 1)

Since I stepped into the role of SCO’s Coordinator of Minority Recruitment, I have gleaned a few key lessons about effective and not-so-effective practices. I can sum them up as the three Cs of URM recruitment: communication, connection and culture.

Communication

Communication with students

Currently, points of interest during my recruiting trips include honors colleges, pre-optometry or pre-health-professions organizations and science classrooms at historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and predominantly white institutions. Initially, I had hit the ground running by attending as many health fairs as possible during my designated recruitment weeks. It has been documented that effective recruitment strategies include attending health career fairs, speaking to campus organizations and participating in career days.5 However, I noticed, at a career fair, where participants do not necessarily know about optometry, convincing one person at a time to visit your table is not an efficient way of swaying the campus mindset about pursuing optometry. Current education research confirms this. Instead of attending career fairs to see which careers match their interests, today’s students attend career fairs to learn more about institutions in which they already have an interest.6 Therefore, I began gearing my visits to cast a wider net. I experience the best results when I speak to groups of health-profession-minded students in a conversation setting. The ability to convey enthusiasm for optometry while fielding questions in a more receptive environment increases interest and curiosity among students and advisors. More inquiries and follow-up questions come from this type of setting compared with the standard health career fair. However, health fairs do remain a useful option because the personal, face-to-face interaction is critical for building relationships, but other options may be more suitable for efficiency.

Communication with college advisors

Another area where strong communication and relational ties are invaluable is with campus advisors. When I contact advisors, many seem interested. Some are excited to hear about a profession in the “allied health” field because they understand not all of their students are interested in or suited for medical or dental school. Surprisingly, it was common for me to reach out to an advisor numerous times before I received a response. As I visited schools where inroads were more difficult to establish, more than one advisor explained that they evaluate the intent of recruiters. Is the recruiter here just to raise his or her own institution’s minority numbers, or because he or she has a genuine interest in the students? Particularly at the HBCUs I visited, I found I needed to cultivate a level of trust. Advisors and the pre-health office tend to develop significant bonds with their students, and they want to ensure they are well taken care of at professional school. When I reach out consistently and work to develop a relationship with the advisors, they eventually begin to contact me as well. Be forewarned: Once a trusting relationship develops with an advisor, the speaking audience becomes larger and larger. This past fall, I spoke about optometry to more than 200 minority science students at Prairie View A&M University ― quite an adventure for me!

Communication with high school counselors

Reaching out to high school counselors is another tool for delving into the pipeline of students and increasing recruitment. However, in my experience, most counselors do not initially respond to e-mails. Results improve when phone calls are made or visits are scheduled. While this is time-consuming, once the relationship develops, e-mail communication is sufficient. This becomes extremely valuable when I am coordinating visits to SCO or developing summer programs.

Connection

Building a connection with prospective optometry students usually takes time. To build and preserve the connection, it is imperative to ensure the door for communication remains wide open after the recruiter leaves the campus. Developing summer programs that invite competitive students to your campus is one of the best ways to create the connection students as well as advisors. If possible, programs should be paid for by your institution or by grants. So many other professions offer no-cost summer programs that for students with limited resources they have become not only crucial but expected. ASCO offers a diversity mini-grant program, which is a valuable resource for the schools and colleges of optometry. When advisors see the optometric institution investing in their students, without increasing the students’ financial burden, unseen barriers break down. Summer programs also allow students to witness optometry in a more detailed setting, which solidifies aspirations to pursue it as a career.

Another program SCO developed to enhance connections invites advisors to an expenses-paid open house to experience optometry and get a glimpse of optometric education in action. This investment is invaluable! Once advisors gain a better understanding of the optometry school application process and the education of an optometrist, they return to their campuses throughout the country as promoters of the career as an option.

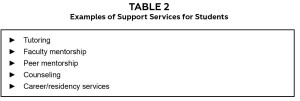

Culture

When presenting the optometry career option to prospective students, it is important to express the culture of the profession and school that will facilitate a good match for the students. Information about support services (Table 2) such as tutoring, peer mentoring and faculty mentoring may reduce anxiety about transitioning to professional school. Such services reflect the institution’s commitment to the success of its students. The supportive atmosphere of the optometry school should be discussed, and it is essential to convey what cultural resources are available in the region of the school.

Table 2. Click to enlarge

Support systems or lack thereof can make or break the transition to professional school and the education experience.5,7 For example, if a student has expressed an interest or hobby, and the recruiter offers to send him or her local information about it, it shows the recruiter cares about the well-being of the student. Another way to communicate cultural cooperation is to provide information about the optometry school’s chapter of the National Optometric Student Association. Taking these types of steps portrays the community support that is vital for the students’ success.8

Conclusion

In my experience, the beauty of adventures in minority recruiting is that the adventure never stops. The ability to influence others toward choosing this profession is exciting. Utilizing communication, connection and culture during this process has a positive effect on the recruitment of under-represented minorities.

References

- Chen EE. Comparing proportional estimates of U.S. optometrists by race and ethnicity with population census data. Opt Ed. 2012;37(3):107-114.

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, Vela MB. URM candidates are encouraged to apply: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):405-412.

- Acosta D, Olsen P. Meeting the needs of regional minority groups: the University of Washington’s programs to increase the American Indian and Alaskan native physician workforce. Acad Med. 2006;81:863-870.

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907-915.

- Knueppel K, Szczotka L. How can optometry become more effective in recruiting and retaining appropriate numbers of underrepresented and disadvantaged students. J Am Optom Assoc. 1992;63(11):802-804.

- Scott M. Op-ed [Internet]: Career fairs are not dead. c2016 [cited 2016 Aug]. Available from: https://www.naceweb.org/talent-acquisition/student-attitudes/op-ed–career-fairs-are-not-dead/.

- Odell M, Mock JJ. Ed. A crucial agenda: making colleges and universities work better for minority students. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 1989.

- Odem KL, Roberts LM, Johnson RL, Cooper LA. Exploring obstacles to and opportunities for professional success among ethnic minority medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):146-153.